The ending of the old fable, “The Little Red Hen”, always bothered me. I don’t know how many versions of the story there are, but I read the “Little Golden Book” version as a child. It was an old book: The golden tape on the binding of the book was broken in places, and the pressed paper-board showed through. So many people must have read it before it came to me!

For those who aren’t familiar with it, the main character is Red Hen. She intends to bake bread, and starts from absolute zero by planting the wheat. She asks for help with the planting, but all of her friends and neighbors are too busy to help. This concept is repeated each time a new task presents itself, from caring for the garden, to harvesting, grinding, and finally baking the bread.

No one will help the little Red Hen, so she does it “all by herself.” In the end, when everyone gets hungry, and approaches her for bread, she denies them. She responds, “Every time I asked you for help, you refused. I had to do it all by myself. So now that the bread is finally baked, I will eat it–all by myself.”

As a child, I put myself in her position, and thought: “Wasn’t she lonely, eating alone? Didn’t the bread stick in her throat when she thought of her starving friends?” What a perfect time to show mercy! And if mercy were uncalled for in this situation, doesn’t it call into question all occasions in which people ask for mercy? It is sad when someone refuses to help you with your work, but how shocking to find that disappointment leads you to withhold bread from your neighbor in need!

On the other hand, how could she justify outright giving them the bread that she had worked so hard to make? How could that be fair?

As a child, I didn’t find a good resolution in my mind, so I put it to the side. But as a parent, I had to find a way to explain the subtleties of the situation to my own children. When should you show mercy? How can we work to even things up so that we don’t take advantage of each other?

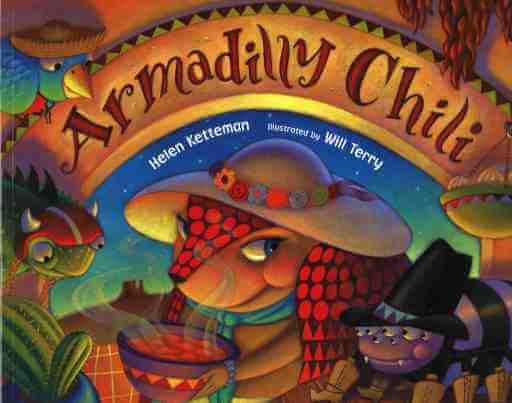

Then I found Helen Ketteman: A joyful, whimsical writer who answers the above questions with a twist of rhyme and a splash of poetry. We stumbled on her book, Armadilly Chili, in the library. The wonderful illustrations caught my son Beau’s eye (he was sevenish at the time), and we were all entranced with the story!

What Helen Ketteman has done is take the elements of the “Little Red Hen” story and put them in a metaphorical kaleidescope, changing the variables to create a fanciful, satisfying story that promotes hard work and initiative, but also deals compassionately with the (assumed) problems of laziness, greed, busyness, and lack of preparation.

In Armadilly Chili the main character is an armadillo named “Miss Billie” instead of a hen, and the goal is to make chili instead of baking bread. No one will help; and when the wonderful chili is done, and the aroma wafts from her home, her friends come knocking at her door. Now Miss Billie has to decide what to do. At this crucial junction, Helen Ketteman gives her “story kaleidescope” a wrench to the right, and views this classic plot with a new set of variables.

Voila! A fair-yet-compassionate result is achieved.

While the neighbors in both stories are hungry and wanting to share, Little Red Hen’s neighbors are freeloaders with nothing to offer; but Miss Billie’s neighbors are well-rounded critters who come with an apology–and a gift! (If I remember correctly, one of the neighbors actually brings a loaf of bread!)

One by one, each neighbor expresses regret for not helping, then produces a treat to make the apology real. The story ends with complete reconciliation followed by a fabulous potluck. Yes!!

How better to illustrate that we all have something a little bit different to contribute, and that our meal can become much more varied and satisfying when we all eat it together? (Not to mention the freedom each character has to pursue their own destiny and create the dish they like best instead of being forced to make what one character wants!)

So I thought of this “story kaleidoscope” that Helen Ketteman uses, changing certain variables and then plugging them into classic story frameworks, and I realized that this is a tool that everyone can use, regardless of whether they are a writer or not.

Sometimes when we have to assume something, because we don’t have all the information, our hidden fears influence those assumptions.

If someone doesn’t answer us right away, for example, we may assume they are rejecting us. But that may not be the case at all. There are a whole host of reasons why someone may not answer us right way, and if we knew some of those reasons, we might end up being compassionate instead of feeling victimized.

See, we just don’t know enough about people to judge their motives, and we have no right to judge their worth. Doing those things puts us into direct conflict with God.

“. . .for man looks at the outward appearance, but the Lord looks at the heart.” –I Samuel 16:7b

We all need grace. When we find ourselves jumping to a conclusion about someone’s motives, remember that those assumptions are something we can control (as soon as we realize we have them!) Why not actively look for a way to paint your neighbor in a good light?

“Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy.” Matthew 5:7

If we give our neighbor the benefit of the doubt, and they don’t deserve it, that’s mercy. But if we assume the worst, and they don’t deserve it, now what? How would we feel toward someone who did that to us?

In her re-telling of The Little Red Hen, Helen Ketteman tweaks the narrative and allows Miss Billie to see her friends and neighbors as whole people, capable of making mistakes, and also able to make restitution and offer (and accept!) forgiveness. Oh, I love this writer!

Go read Armadilly Chili, and then feel free to browse the library of wonderful classic tales retold by Helen Ketteman. (You really must look her up and read every one of her wonderful books! Even if you don’t have young children, you will not regret it!)